It is a very modern dilemma. Should you hand your child a smartphone, or keep them away from the devices as long as possible?

As a parent, you'd be forgiven for thinking of a smartphone as a sort of Pandora's box with the ability to unleash all the world's evils on your child's wholesome life. The bewildering array of headlines relating to the possible impact of children's phone and social media use are enough to make anyone want to opt out. Apparently, even celebrities are not immune to this modern parenting problem: Madonna has said that she regretted giving her older children phones at age 13, and wouldn't do it again.

On the other hand, you probably have a phone yourself that you consider an essential tool for daily life – from emails and online shopping, to video calls and family photo albums. And if your child's classmates and friends are all getting phones, won't they miss out without one?

There are still many unanswered questions on the long-term effects of smartphones and social media on children and teenagers, but existing research provides some evidence on their main risks and benefits.

In particular, while there is no overarching evidence showing that owning a phone or using social media is harmful to children's wellbeing in general, that may not tell the full story. Most research so far focuses on adolescents rather than younger age groups – and emerging evidence shows there may be specific developmental phases where children are more at risk from negative effects.

What's more, experts agree on several key factors to consider when deciding if your child is ready for a smartphone – and what you should do once they own one.

The evidence on when is the right time to give a child their own smartphone is poor, but there are key moments where the risks are higher (Credit: Nicolas Asouri/AFP/Getty Images)

Data from Ofcom, the UK's communications regulator, show that the vast majority of children in the UK own a smartphone by the age of 11, with ownership rising from 44% at age nine to 91% at age 11. In the US, 37% of parents of nine- to 11-year-olds say their child has their own smartphone. And in a European study across 19 countries, 80% of children aged nine to 16 reported using a smartphone to go online daily, or almost daily.

"By the time we get to older teens, over 90% of kids have a phone," says Candice Odgers, professor of psychological science at the University of California, Irvine, in the US.

While a European report into digital technology use among children from birth to eight years old found that this age group had "limited or no perception of online risks", when it comes to the detrimental effects of smartphone use – and social media apps accessed through them – on older children, solid evidence is lacking.

Odgers analysed six meta-analyses looking at the link between digital technology use and child and adolescent mental health, as well as other large-scale studies and daily diary studies. She found no consistent link between adolescents' technology use and their wellbeing.

"The majority of studies find no association between social media use and mental health," says Odgers. In the studies that did find an association, the effect sizes – both positive and negative – were small. "The biggest finding really was a disconnect between what people believe, including adolescents themselves, and what the evidence actually says," she says.

The only person who really can judge how social media affects children is often the one closest to them – Amy Orben

Another review, by Amy Orben, an experimental psychologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, also found the evidence inconclusive. While there was a small negative correlation, on average, across the studies included, Orben concluded it was impossible to know whether the technology was causing the dip in wellbeing or vice versa – or whether other factors were influencing both. Much of the research in this area is not of high enough quality to deliver meaningful results, she notes.

Of course, these results are averages. "There's an inherent large variation around that impact [on wellbeing] that has been found in the scientific literature," says Orben, and the experience of individual teenagers will depend on their own personal circumstances. "The only person who really can judge that is often the people who are closest to them," she adds.

In practical terms, this means that regardless of what the broader evidence says, there may be children who do struggle as the result of using social media or certain apps – and it's important for parents to be attuned to this, and offer support.

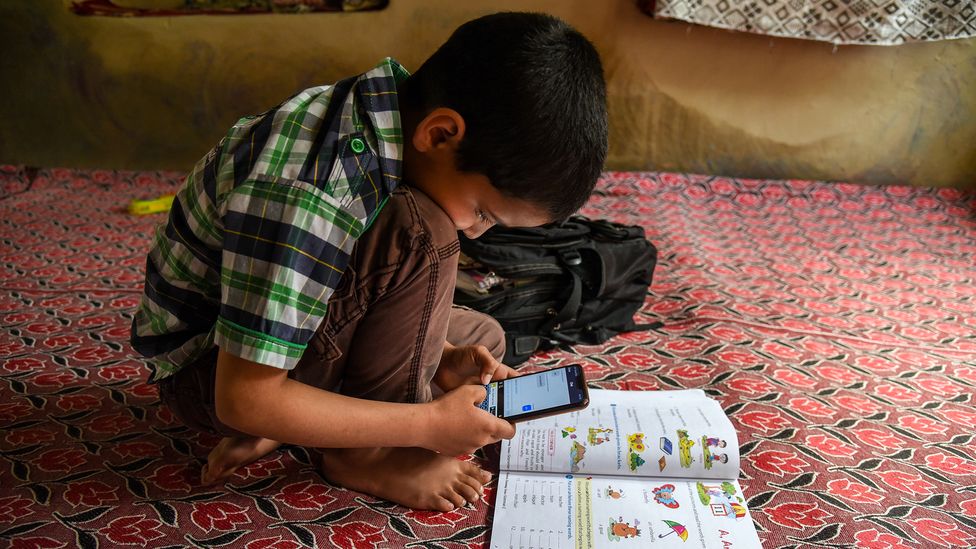

During the pandemic, mobile phones provided a crucial way for children to access online classes while at home (Credit: Idrees Abbas/Getty Images)

IN BRIEF: HOW SMARTPHONES AFFECT CHILDREN

Smartphones are still a relatively new technology in terms of understanding long-term affects, but emerging evidence has revealed some important factors for different age groups:

- Children from birth to eight years old have "limited or no perception of online risks" when it comes to using smartphones and social media apps, a European study across seven countries showed.

- Parents have a powerful influence as role models: children often mirror their parents' smartphone use, the same study found.

- Teenagers may be particularly sensitive to social media feedback. Certain developmental changes during adolescence can mean that young people become more sensitive to status and social relationships, which in turn may make social media use more stressful for them.

- Experts say communication and openness is key when it comes to how parents deal with young people's smartphone use, including talking about what they're seeing and experiencing online.

On the other hand, for some young people, a phone can become a lifeline – somewhere to find a new form of access and social networking as a person with a disability, or a place to search for answers to pressing questions about your health.

"Imagine you are a teenager worried that puberty is going wrong, or your sexuality isn't the same as your friends', or worried about climate change when the adults around you are bored with it," says Sonia Livingstone, professor of social psychology at the London School of Economics, UK, and co-author of the book Parenting for a Digital Future.

For the most part, though, when they're using their phone for communication, children are talking to friends and family. "If you actually analyse who kids are talking to online […] there's a very strong overlap with their offline network," says Odgers. "I think this whole idea that we're losing a kid in isolation to the phone – for some kids, that can be a real risk, but for the vast majority of kids, they're connecting, they're sharing, they're co-viewing."

In fact, while smartphones are often blamed for children spending less time outdoors, a Danish study of 11- to 15-year-olds found some evidence that phones actually give children independent mobility by increasing parents' sense of security and helping to navigate unfamiliar surroundings. Children said phones enhanced their experience outside through listening to music, and keeping in touch with parents and friends.

Of course, the ability to be in near-constant communication with peers doesn't come without risk.

"I think that the phone has been a fantastic unleashing of what was always an unmet need on the part of young people," says Livingstone. "But for many it can become coercive, it can become incredibly normative. It can pressure them into feeling that there is a place where the popular people are, which they are struggling to get into, or might be excluded from, where everyone is doing the same kind of thing and knows about the latest whatever-it-is."

In fact, in a paper published earlier this year, Orben and colleagues found "windows of developmental sensitivity" – where social media use is associated with a later period of lower life satisfaction – at specific ages during adolescence.

For many phones can become coercive – Sonia Livingstone

Analysing data from over 17,000 participants aged between 10 and 21, the researchers found that higher use of social media at ages 11 to 13 for girls, and 14 to 15 for boys, predicted lower life satisfaction a year later. The reverse was also true: lower social media use at this age predicted higher life satisfaction the following year.

This aligns with the fact that girls tend to go through puberty earlier than boys, the researchers say, though there's not enough evidence to say this is the cause of the difference in timing. Another window appeared at age 19 for both male and female participants, around the time that many teenagers leave home.

Parents should take these age ranges with a pinch of salt when making decisions for their own families – but it's worth being aware that developmental changes could make children more sensitive to the negative side of social media. During the teenage years, for example, the brain changes massively, and this can influence how young people act and feel – including making them more sensitive to social relationships, and status.

Many parents choose to introduce their children to social media from a young age (Credit: Richard Baker/Getty Images)

FAMILY TREE

This article is part of Family Tree, a series that explores the issues and opportunities families face today – and how they'll shape tomorrow. You might also be interested in other stories about children and young people's health and development:

- Are sarcastic teens the smartest?

- The biggest myths about the teenage brain

- How we invented the teenager

Climb other branches of the family tree with BBC Culture and Worklife.

"Being a teenager is a really a major time of development," says Orben. "You're much more impacted by your peers, you're much more interested in what other people think about you. And the design of social media – the way that it provides social contact and feedback on, more or less, a click of a button – might be more stressful at certain times."

As well as age, other factors could influence the impact of social media on children and teenagers – but researchers are only just beginning to explore these individual differences. “This is really a core area of research now,” says Orben. “There will be people who are more negatively or positively impacted at different time points. That might be due to living different lives, going through development at different points, they might be using social media differently. We really need to tease those things apart.”

While research can provide food for thought for families deciding whether to buy their child a smartphone, it can't offer specific answers to the question of "when?".

"I think by saying that things are more complex, naturally it does push the question back to the parents," says Orben. "But that might actually not be such a bad thing, because it's so heavily individual."

The key question parents need to ask, says Odgers, is: "How does it fit for the child and for the family?"

For many parents, buying a child a phone is a practical decision. "In a lot of cases, parents are the ones that want the younger children to have phones so that they can keep in touch throughout the day, they can coordinate pickups," says Odgers.

It can also be seen as a milestone on the road to adulthood. "I think for children it gives them a sense of independence and responsibility," says Anja Stevic, researcher in the department of communication at the University of Vienna, Austria. "This is definitely something that parents should consider: are their children at a stage where they are responsible enough to have their own device?"

Set aside time to go though what's on the phone together – Sonia Livingstone

One factor parents shouldn't overlook is how comfortable they feel with their child having a smartphone. In one study by Stevic and colleagues, when parents felt a lack of control over their children's smartphone use, both parents and children reported more conflicts over the device.

It's worth remembering, though, that having a smartphone need not open the floodgates to every single app or game available. "I'm increasingly hearing, when I interview children, that parents are giving them the phone but introducing requirements to check and discuss which apps they get, and I think that is probably really wise," says Livingstone.

Parents could also, for example, spend time playing games with children to make sure they're happy with the content, or set aside time to go through what's on the phone together.

"There's some amount of supervision, but there has to be this communication and openness to it, to be able to support them for what they're seeing and experiencing online, just like offline," says Odgers.

Discussing which apps children can have and how they use their phone can allow parents to support their child's phone use (Credit: Edwin Remsberg/Getty Images)

When setting house rules for smartphone use – such as not keeping the phone in a child's bedroom overnight – parents also need to take an honest look at their own smartphone use.

"Children hate hypocrisy," says Livingstone. "They hate feeling they're being told off for something that their parents do, like using the phone at mealtimes or going to bed with a phone."

Even very young children learn from their parent's phone use. A European report into digital technology use among children from birth to eight years old found that this age group had little or no awareness of the risks, but that children often mirrored their parents' technology use. Some parents even discovered during the study that children knew their device passwords, and so could access them independently.

But parents can use this to their advantage by getting younger children involved during smartphone-based tasks, and modelling good practice. "I think this involvement and co-use, that's actually a good way for them to learn what's happening on this device, what it is for," says Stevic.

Ultimately, when to buy a smartphone for a child comes down to a value decision for parents. For some, the right decision will be not to buy one – and, with a little bit of creativity, children without a smartphone don't have to miss out.

"Children who are reasonably confident and sociable will find workarounds and be part of the group," says Livingstone. "After all, mostly their social life is at school, mostly they see each other every day anyway."

In fact, learning to cope with the fear of missing out they feel by not having a phone could prove a useful lesson for older teenagers when – no longer constrained by their parents – they inevitably buy one for themselves, and need to learn how to set limits.

"The trouble with the fear of missing out is that it's never ending, so everyone's got to learn to draw a line somewhere," says Livingstone. "Otherwise, you'd just be scrolling 24/7."

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List" – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.